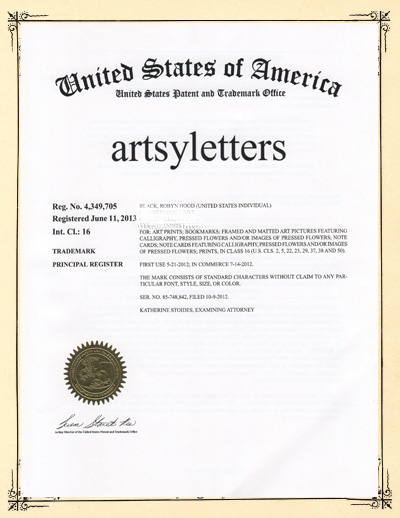

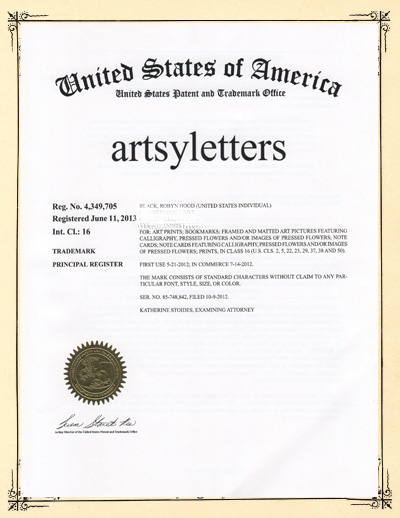

Nice surprise in the mail this week: I’m the proud owner of a new trademark!

A business name does not have to be registered as a trademark, of course. But I wanted to give it a try. My experience was fairly fast and painless as these things go.

When contemplating starting an art business and Etsy shop last spring, I came up with lots of brilliant business names. Only to find online that other folks had come up with said brilliant names long before I. When “artsyletters” meandered into my mind, I was happy to discover I couldn’t find it online. First stop: website domain. Then I opened an Etsy shop with the name, though I wouldn’t add any items to it for a few more months. I got a Facebook page, Twitter account and Pinterest account using it. (Plus a few other social media outlets that I haven’t really set up yet.)

It’s somewhat easier/cheaper to get a trademark if the name is already in use by you in commerce. So I made some sales starting in late summer last year, stocking my Etsy shop and hitting some art shows in the fall. I put my name/logo on all my products and had a banner made for my show tent. Now I was ready to apply for a trademark. Watching the budget, I opted for LegalZoom.

My eyes tend to glaze over with legal-ese, but I was (pretty much) able to figure out the forms. When I had questions, the LegalZoom folks responded in emails or when I called. I decided to apply in an already existing category (International Class 16) that most closely matched what I’m producing, even though I don’t make all of the items in that class (um, pressed flowers?).

They conducted an initial search. This search brings up names of businesses which might cause confusion for consumers, and therefore might keep you from being able to trademark your chosen name. After these results, I opted to upgrade my membership so I could speak with an attorney by phone for 30 minutes before sallying forth. (You can upgrade without any kind of lengthy contract – in my case I did for the first couple-few months of the process so I’d have access to an attorney appointment at a very reduced rate.)

The person I spoke with was very clear, professional, and friendly. He pointed out one other existing business name which might give the USPTO pause when considering mine, because the category of products was similar. He said he thought I had at least a 50/50 chance of getting through the first time, though. With those precarious odds and crossed fingers, I decided to proceed. I filed in October, I believe.

To my delight, my business name was published in the USPTO Trademark Official Gazette in March after its initial review. This means it was “published for opposition.” Well, let me let the USPTO explain it:

If the examining attorney raises no objections to registration, or if the

applicant overcomes all objections, the examining attorney will approve the mark

for publication in the Official Gazette, a weekly publication of the

USPTO. The USPTO will send a notice of publication to the applicant stating the

date of publication. After the mark is published in the Official

Gazette, any party who believes it may be damaged by registration of the

mark has thirty (30) days from the publication date to file either an opposition

to registration or a request to extend the time to oppose.

I never discovered any objections, and I got the lovely certificate above in the mail this week. The entire process can take from six months to a year, and in some cases, longer. I was happy to enjoy pretty smooth sailing for mine. The whole process cost me somewhere in the neighborhood of $500, with the very modestly priced phone consultation tacked onto the registration fees.

If you decide to pursue it for your business, be prepared for some other interesting mail to come your way. I’ve had several letters from entities whose return addresses are countries in Eastern Europe, claiming to offer international “filing” or “registration” of my US trademark, all for say, a few thousand dollars. I love the fine-print disclaimer that came in one yesterday: “...please notice that this registration has not any connection with the publication of official registrations, and is not a registration by a government organization….” – yet the “fee” was $2327.00. (!)

Please also note that this little ramble in absolutely no way whatsoever constitutes any sort of legal advice, which I am unabashedly unqualified to dole out. (Also, no animals were harmed in the composition of this blog post.) But I wanted to share this little piece of my journey for other indie artists/interested folks out there. Thanks for coming along!